Blog Archives

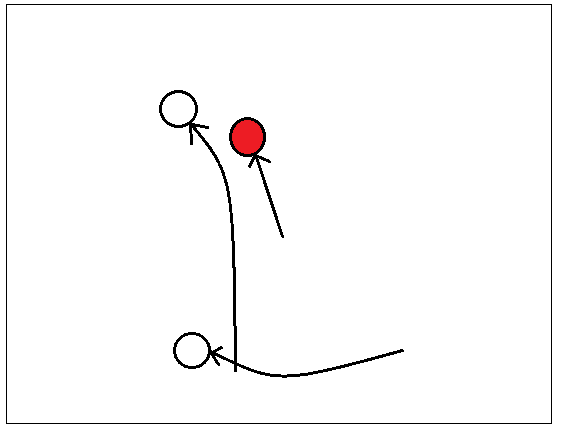

Y Corner/TE Fade (5th Grade/10u)

Our Y Corner play is a play action passing concept that releases the short side end on a corner route that is often uncovered by the defense over-reacting to Power in the opposite direction. Using a taller player with goods hands also creates a mismatch opportunity as most youth teams put smaller-fasters in at defensive backfield positions.

Play Action Passing Concept

Used against Man or Zone

This concept is related to Spacing in that it attempts to draw a coverage player off his man or a coverage zone in order to support an illusory running play. Our “Y Corner” is a form of Play Action by design.

Enhancing the Football Running Game with the Passing Game

At a bare minimum, establishing at least the threat of a passing game is critical against the best opponents. For C gap running teams like us, the lack of a passing threat invites the defense to put 10 in the box and crash their edge players in like a vice. They’ll end up squeezing all the space out of the C gap leaving us nowhere to run. The solution is to exploit the weakness they present when over-playing the run. It sounds simple.

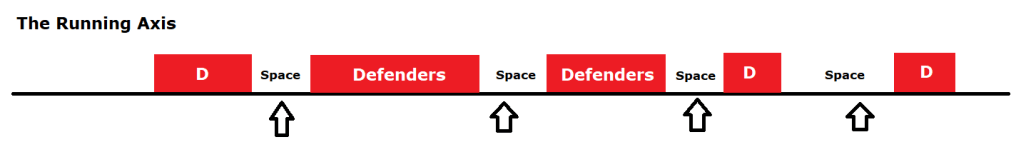

Running the ball is a one-dimensional science in that running plays attack a point along a single line that extends left and right. Nerds describe this as a single “axis”. Running plays work positively by pushing the defenders away from or sealing defenders off from a point on that line (as with Power, Blast, Sweep plays). Or they work negatively by drawing off and spreading defenders apart along the line to create opening points (as in misdirection and stretch plays). All running play designs use one or a combination of both of these concepts.

Now, some nitpicker out there might suggest that running is two-dimensional in that successful blocking must address additional levels of the defense. But this is success is achieved sequentially, not simultaneously. The run must pass through the first line before it can pass through the second. Stated another way: a running play cannot attack the secondary level before it breaks through the front. Therefore, running is just a sequence of one-dimensional events.

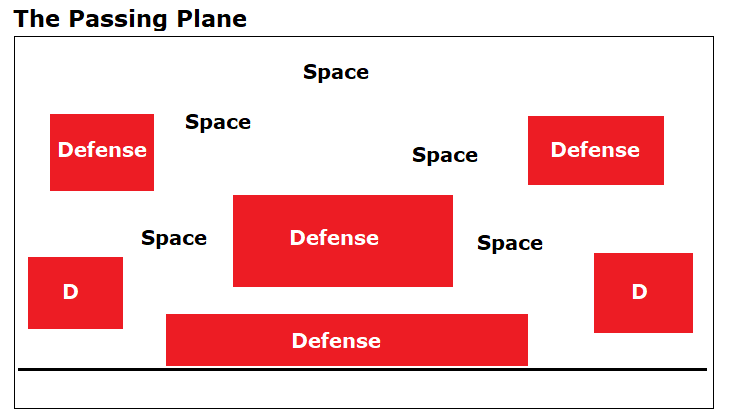

Passing, on the other hand, is two-dimensional in that it is capable of attacking forward, into the defense, in addition to left and right. It can be said that passing exists on two axes, also known as a plane. This forces the defense to defend this two-dimensional space rather than just a line.

Our ability to force the defense to cover two-dimensional space is useful to draw the defenders OFF the running axis or AWAY from specific points on the running axis. The more effective our pass plays, the more the defense must honor them and the more effective our running game should be as a result.

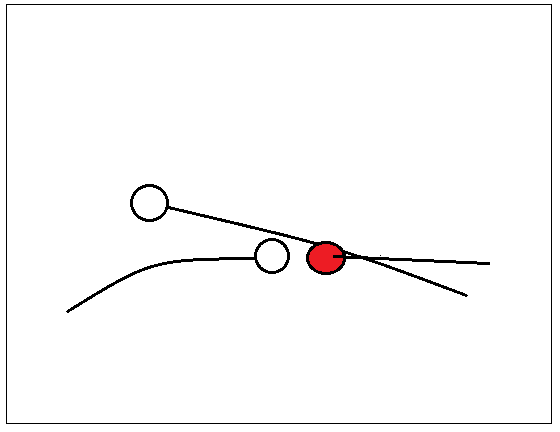

An area (or plane) is vastly more difficult to defend than a line. But the offset is that throwing and catching is vastly more difficult than running. To be successful, a receiver must obtain enough open space in which to catch the ball without it being knocked away by the defender. The talent of the receiver and the QB, relative to the defenders, determines how much open space must be obtained. This exercise is simple for a team with a really fast kid and a QB with a strong, accurate arm versus a defender not as gifted. In this scenario, there is no coaching necessary beyond “throw the ball to the fast kid.” This is the simplest passing concept– the Mismatch. Unfortunately for most of us, we don’t usually have access to this advantage and we must design ways to get our receivers open. This process is where offensive coaches encounter another limitation: Time. Typically, the less the athletic advantage the offense has, the more complex the play designs must be to get receivers open in time. But the more complex the play design, the more time it takes to execute it. This tradeoff limits the consistency and effectiveness of almost all youth and most high school passing systems primarily because pass blocking is generally reactive and difficult to teach and thus QBs have very little time.

To prevent offensive players from obtaining the ball in one of these spaces, the defense can implement one of two (or both) of the following tactics. They can attempt to eliminate the spaces in a locational manner by assigning defenders to locations (aka “zone”) or they can eliminate spaces directly by assigning defenders to the receivers so that the open space is eliminated wherever they go (aka “man to man”).

Offenses use receiver routes to attempt to exploit the spaces the defense leaves in the pass coverage plane. The combinations of possible receiver routes can be aggregated into a single “route tree” that can be leveraged to make play calling more dynamic and flexible.

…but the defense is not static and will adjust to the receivers moving towards the openings (zone) or simply deny the openings by player assignment (man). Thus, a route tree alone will not get a receiver(s) open (unless the defense is unsound or there is a Mismatch coverage situation). Therefore, a COMBINATION of routes must be applied where at least two routes are working together to create space for at least one of the receivers. We call this a “Route Concept”.

To get receivers into space using a Route Concept requires time. The play design must increase the time available to throw or reduce the time required to get open or some combination of the two. The time to throw can be lengthened by the design of the protection or by the movement of the QB (i.e. a rollout, for instance). The time required for the receiver to get open is a function of the route combination. During grade school recess football, everyone is a receiver or pass defender except the QB. There is typically no pass rush and no pass blocking is needed. The QB has infinite time– at least until the bell rings ending recess. The primary Route Concept employed in recess football is “just run around until you get open.” In structured football, the QB has only a few seconds at best. Thus, Route Concepts must be executed successfully within a very short span of time.

So what are the Route Concepts that can be applied by route combinations to get receivers open? It seems to me they really fall into only a few categories:

Mismatch

Used against Man or Zone

As mentioned, this is where a faster, bigger, stronger kid can make his own space to catch a ball by simply running past, leaping over, or out-muscling a weaker defender. This is the dominant passing concept at the youth level. It is a perfectly valid tactic that every coach should exploit if available to him as it is the simplest to implement. Jump balls, go routes, and 50/50 balls are examples of mismatch. If no other route concept is employed, then the route concept is based upon Mismatch by default.

Obstruction

Used against Man

This concept seeks to create receiver space by obstructing the covering defenders (within the framework of the rules) to create open space for the receiver to catch and run. Mesh, rubs, and screens utilize this concept.

Conflict

Used against Zone

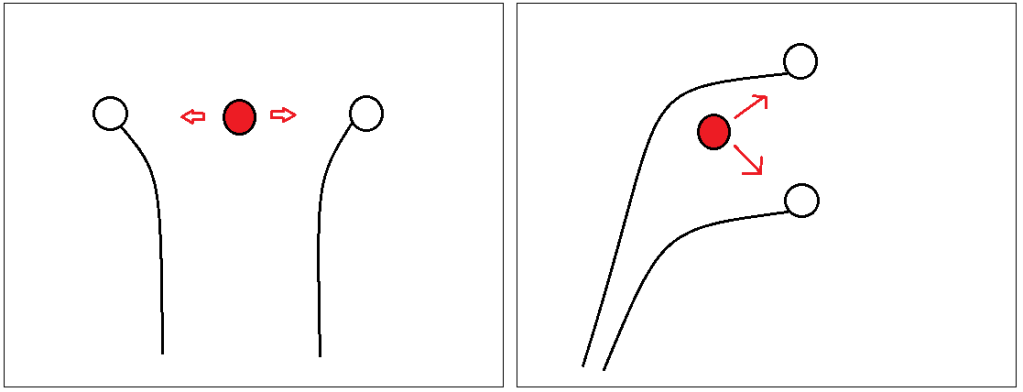

This concept seeks to force one defender to choose one of two possible receivers to cover (or forces two to cover three or three to cover four). The choice is presented simultaneously. If he chooses one, the another receiver will be open. Levels, drive, and four verticals, as well as scissors route combinations are examples of creating Conflict.

Spacing

Used against Man or Zone

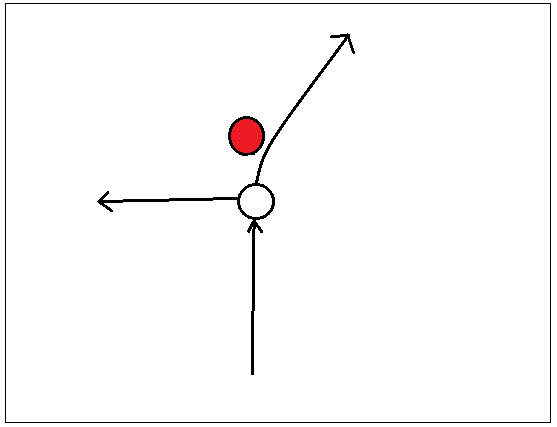

This concept seeks to create space for one receiver with the route(s) run by another. It is similar to conflict but is sequential rather than simultaneous. The first route draws off the defender and the open space is then backfilled by another receiver. A clear-out, swing, wheel, checkdown, and crossers are forms of spacing.

Play Action

Used against Man or Zone

This concept is related to Spacing in that it attempts to draw a coverage player off his man or a coverage zone in order to support an illusory running play. Our “Y Corner” is a form of Play Action by design.

Choice

Used against Man

This concept gives an option to the RECEIVER who is reading the play of his defender. If the defender tries to take away A then the receiver exploits B. The run-and-shoot offense uses Choice routes extensively.

All route combinations attempt to leverage at least one of these six concepts. And they all must be executed within the context of limited time. The longer the design concept takes to develop, the greater the risk of play failure. The less athletic the offense (compared to the defense) the better the execution and timing is required to be successful. This requires reps, reps, reps, reps, reps. It is for this reason that we deem route trees to be of little marginal value IN GAME at our level. For most teams at amateur levels, introducing a novel route combination, mid game, by referencing an abstract route tree, ignores the critical importance of timing and execution that can only come from numerous practice reps. We think our passing game will be better served by adding a “Choice” route or a tag that adds an additional route to the existing plays’ route combinations rather than grab-bagging passing route combinations in the middle of a game.

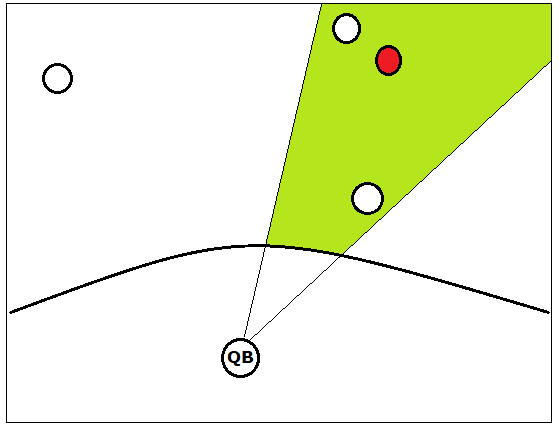

Ideally, each route combination must also attempt to simplify the read of the QB. The more complex the read, i.e. the greater the range that the QB must view and process, the longer it will take to compute, and the greater the risk of play failure. If a QB’s total viewing range is 180 degrees from left sideline to right sideline, then an amateur QB should probably not be asked to read more that a quarter of it (or 45 degrees) on any given play. Consideration must also be made for obstructions of view such as linemen as well. This can make the mesh, crosser, and drive route concepts that break open in the middle of the field, in front of linemen, difficult to see and read for a younger or shorter QB.

Lou Holtz once said that “a team could put a receiver on the field with no arms and the defense will assign someone to cover him.” This has profound implications for play design! It implies that you can occupy (or remove) at least one defender from the play with a player you never intend to throw the ball to. In theory, you can remove a defender from the running axis without even intending to pass. We try to use the routes outside the narrow QB read window to draw defenders off based on the Lou Holtz premise. If the defense simply stops covering a kid, then it’s my job as coach to spot that and throw him the ball on a later play to make the defense pay. This is at the root of play-calling art and it is difficult, especially when viewing from the sideline. Anyone can call plays. It takes skill to call the RIGHT plays. Skill comes from experience. It takes lot’s of practice and discipline to train the eye to focus on the defense rather than on the ball.

We pass to open up the run and we believe passing is necessary to beat the best teams. Forcing the defense to play in a two-dimensional plane, rather than one dimension, will draw defenders off the running axis and make running the ball easier. If we can get kids open and just throw the ball at them (they don’t even need to catch it) the defense will be worried enough about it to honor the pass and pull defenders off the running axis. In the absence of the availability of a receiver mismatch, we must apply thoughtful route concepts to route combinations to get receivers open. I think any passing offense would do well to build a passing game with route combinations based on at least three of the concepts indicated above rather than just relying on a mismatch. Most importantly, any lower level passing system should be simplified as much as efficiently possible.

If you think I’m missing something let me know in the comments. I do not claim to be a passing expert. This post is part of my journey towards furthering my understanding of this great game. Likes are appreciated if it was interesting or useful.